Editor’s note: this is a guest post from Michael Wilson.

We here at 4LN are ardent supporters of spoiler warnings. No one wants their gleeful anticipation of a topic’s reveal marred by the unexpected gift of knowledge. That being said, if you’re at a website with the word “nerd” used endearingly in its title and are expecting a spoiler warning regarding the events of Star Wars, Episode IV: A New Hope, you may be at the wrong website. However, as a kindness, we will issue the following to preface this article:

WARNING! POTENTIAL SPOILERS AHOY!

There is an important period in literary history dominated by a name that has becomes its own sort of archetype: Billy Shakespeare, or William Shakespeare, depending on who you ask.

Shakespeare’s works hardly need an introduction. Many of us were force-fed his plays as early as grade school. Some of us were even made to memorize famous monologues and sonnets to achieve certain grades. While there is a group for whom this subject brought on bouts of drug-like induced drowsiness, there is another group that felt quite the opposite. Relishing in the evocative language and thrilling to the stories of human behavior and history. The latter group seems to be the more persistent of the two, as Shakespeare has never seemed to fade in popularity.

It is because of this persistent popularity that we find so many of Shakespeare’s works reimagined with some sort of novel or modern take on the stories. Just look at the eloquence of 10 Things I Hate About You when Heath Ledger asks Julia Stiles if she owns black panties. (But really, that movie was an adaptation of Taming of the Shrew, and while I don’t remember there being a reference to “undergarments so dark as to be cloaked in shadows,” I’m sure there’s something like that in there somewhere.)

The same sort persistence also brings us unique looks at works having little to nothing to do with Shakespeare. Certain bright minds with a command of the English language take their time to create something beautiful for the rest of us wallowing in our grunts and belches. One such bright mind is Ian Doescher.

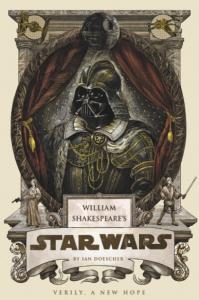

Doescher is the author of William Shakespeare’s Star Wars: Verily, a New Hope. What this brilliant and kind man has done is taken the story of Star Wars, Episode IV, a story memorized by every red-blooded human and wookie, and has retold it in the style most associated with Billy Shakespeare: iambic pentameter. This is a fusion of two huge nerd icons that, under the deft hand of Doescher, brings us something nothing less than fantastic.

Through this method of storytelling we are given an opportunity to revisit a story and characters from a wholly new perspective. Before even opening the book to begin this story there is a burden of knowledge in regards to the plot. That knowledge does not keep one from enjoying this story as though it were new.

With the use of several elements foreign to the movie, we are exposed to new depths of the story. The very first element we’re exposed to is the Chorus. This is a character, used especially in Elizabethan plays, whose function is to speak a prologue and give context to events taking place. We first see the Chorus speaking its version of the famous text scrolling from the original film:

It is a period of civil war.

The spaceships of the rebels, striking swift

From base unseen, have gain’d a vict’ry o’er

The cruel Galactic Empire, now adrift.

Amidst the battle, rebel spies prevail’d

And stole the plans to a space station vast,

Whose pow’rful beams will later be unveil’d

And crush a planet: ‘tis the DEATH STAR blast.

Pursu’d by agents sinister and cold,

Now Princess Leia to her home doth flee,

Deliv’ring plans and a new hope they hold:

Of bringing freedom to the galaxy.

In time so long ago begins our play,

In star-crossed galaxy far, far away. (Prologue.1-14)

Did you feel that? That mounting joy as you read that? The goosebumps culminating up to the very end, with “far, far away”? Yeah, you felt that.

As you read the play, having in your mind how this might actually be brought about on stage, the importance of the chorus increases. It introduces characters and scenarios in a way without the use of cameras and editing tricks. Here’s another bit introducing the Tusken Raiders while Luke and C-3PO are searching for R2-D2

While droid and man go racing ‘cross the sand,

The Tusken Raiders watch the two pass by.

Their banthas mounting, gaffi sticks at hand,

They heave unto the air their warring cry. (II.i.67-70)

It’s easy to imagine this scene from the movie, and the Chorus aids us in taking that imagination and applying it to stage play. This occurs throughout the play. We might see Luke and C-3PO standing close by the Tusken Raiders, but the Chorus gives us the context to understand that the audience is meant to interpret distance between the two, where one might still be oblivious to the presence of the other. It engages the audience by informing them of what they are seeing against what the story would have them perceive.

The chorus is hardly the only element engaging the audience. We also have the use of characters addressing the audience, destroying the fourth wall. The most noticeable instance of this is when R2-D2 (whose lines primarily consist of beeps, meeps, and boops–both in the movies and the play) turns to address the audience early in the play, just after C-3PO enters the escape pod destined for Tatooine.

This golden droid has been a friend, ‘tis true,

And yet I wish to still his prating tongue!

An imp, he calleth me? I’ll be reveng’d,

And merry prank aplenty I shall play

Upon this pompous droid C-3PO (I.ii. 57-60)

He (she? No, surely he.) goes on stating that “I clearly see how I shall play my part” (I.ii.66) in regards to the rebellion, but in the first bit of his short monologue we already see a character development of R2-D2 that we see play through the rest of the trilogy. He’s been established as an important component to the success of the protagonists, but he’s also being established as a prankster character, in a way reminiscent to Shakespeare’s Puck from a Midsummer Nights Dream.

This same technique allows us brief insights into the thoughts of other characters as well. When Luke questions Obi-Wan on the manner of his father’s death he speaks [aside:], as though to himself. Only the audience hears his words, and only they benefit from them.

[aside:] -O question apt!

The story whole I’ll not reveal him,

Yet may he one day understand my drift:

That fromt a certain point of view it may

Be said my answer is the honest truth.

[To Luke:] A Jedi nam’d Darth Vader–aye, a lad

Whom I had taught until he evil turn’d–

Did help the Empire hunt and then destroy

The Jedi. (II.ii.68-75)

Here we see mechanisms behind choices that would not normally be illuminated until much later, if at all. As an already established fan of the franchise this permits us a closeness of understanding that can be much more appreciated.

Of course, some of the best parts of this play that is Star Wars are some of the simple lines reworked from the movie. Obi-Wan’s description of a lightsaber is nothing short of awesome:

It is the weapon of a Jedi Knight:

If thou in thine own hand could hold a sun,

Then thou wouldst know the power of this tool. (II.ii.51-53)

Okay, so we’ve established that using a lightsaber is like welding a freaking sun. We didn’t get any of that from the movie. Just that it wasn’t clumsy like a blaster and that it was for a civilized age. Sure, that’s all true–but where was the part about holding a weapon that could be described as having the equivalent power of a celestial body generating 400 trillion trillion watts. Doescher gave us this, and for that we love him.

The play is filled with wonderful moments like the above. Monologues from the characters are scattered throughout the pages, and they truly offer an insight into the sort of characters and plots we’re dealing with here. Doescher knows when to have fun with the fans in other ways, though. Here’s the famous scene in which Greedo and Han have a shot at one another, let’s see who shoots first.

HAN:

Aye, true, I’ll warrant thou hast wish’d this day.

[They shoot, Greedo dies.

[To innkeeper:] Pray, goodly Sir, forgive me for the

mess.

[Aside:] And whether I shot first, I’ll ne’er confess!

[Exuent. (III.ii.160-65)

What a way to address the “Han shot first” rabble. No sides chosen, just a coy remark coneding no guilt for either party–the matter left to discussion. Well done. Just so well done.

We could spend another several hours giving favorite examples for this work of art, but the play itself, in its entirety, is a favorite example. You’ll just have to read it. This is one of those few books that you can pick up and after reading just the brief prologue you know that you’ll either love it, or that you are something soulless who can witness no happiness in the world.

WORKS CITED

Doescher, Ian. William Shakespeare’s Star Wars: Verily, a New Hope. Philadelphia: Quirk, 2013. Print.

Knowledge, Dr. “How Much Energy Does the Sun Produce?” Boston.com. The Boston Globe, 5 Sept. 2005. Web. 6 Sept. 2013.